It started as a routine business flight; after a long weekend of meetings, I grab an overpriced, TSA-approved snack in the airport and settle into my window seat, ready to enjoy a movie or book on the way home. I'm usually so spent after these weekends that I rarely do more than nod and smile at my seat mate(s), preferring the quietness of my noise-cancelling ear buds to chatting.

But this time was different: the middle seat was still empty, and just before the plane doors were to close, a long-haired man boarded the plane with a paper sack from the co-op where I shop at home. And he plopped down in the middle seat and flashed a friendly smile. As we took off, he reached in his paper bag, and pulled out hummus and chips, and offered some to me. I demurred, but had to ask him how he got the hummus past the TSA. He shrugged, but we struck up a conversation.

Turns out we were both in Chicago for work; I was fortunate to work inside during the bitterly cold January days, while he was supervising building houses. He was headed home to see his son, who was hoping to grow up to be a fireman. Funny thing, I said, so is my older boy, who is at college studying fire science. I tell him about the great fire explorer program close to where his son lives, we chat some more, and the conversation ebbs a bit.

I pick up my tablet to open a book, and the splash screen is a picture my son sent me of the present I had given him for Christmas--a real fire helmet for his volunteer firefighting job. I had ordered in online to his specs, but had it delivered so had asked for a picture. So I turn to my seat mate, and say, see, here's the helmet I bought my son for Christmas.

"No way!" he says. Confused, I ask what he means. He starts digging in his pockets and pulls out his passport. His surname is Hellstern, the same as my husband and son--whose name is emblazoned on the fire helmet. An extremely rare name, with its origins in the little town of Betra, where my father-in-law was born. And this is the first time I have met anyone outside of our immediate family who bears this name.

I tell seatmate all this, and he is intrigued: he knows some of his family history back a generation or two, but we find no immediate connection. As the plane lands, we exchange emails, and I promise to share the Hellstern tree with him, and to find out how they are connected.

(As a funny aside, when I told this story to my husband on my return, his reaction was the same "no way!" that I had heard on the airplane.)

It takes a couple of years of research and exchanges, but the connection is made: he and my husband are eighth cousins; I send all of the family research on his branch to my former seatmate, and we add another name to the standing invitation list. A new cousin, who made a routine flight anything but routine.

|

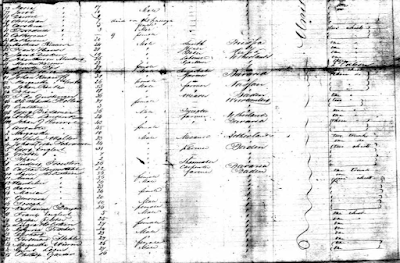

| A happy immigrant couple, three generations back from my seatmate |