The vast majority of genealogical research comprises seeking out documentation: certificates that give us birthdates, marriage (and divorce) dates, and death dates (and where the bodies are buried). We fill in with snapshots of the family unit with censuses (with notable lacunae in the 1890 US Census, and San Francisco and Irish records lost to fire). If we're really lucky, their names may pop up in the newspaper--something as mundane as a property transfer, or, maybe something substantive, like a golden anniversary celebration or obituary. All of these can be documented and have a place in the GEDCOM data structure.

To that framework, we can make a few assumptions: the span of time between a marriage and the birth of the first child is usually a bit more than nine months--though sometimes it is significantly less. Sometimes a family heirloom will mark a date and furnish additional clues: a diploma, a journal, letters to distant family members about how things are going, and memoirs (almost always unfinished).

But the hardest question to answer is rarely "when?" or "where?" or even "with whom?"; it's "why?"

This is where we rely on history and family lore--oral hints passed down the generations, each with the projections and interpretations of the teller, combined with an understanding of what was happening in their world. Sometimes it's obvious: a holocaust survivor immigrating to Israel, an Irish family fleeing the potato famine, someone chasing gold in 1849. But most of the time, the motivation for these great leaps of courage--leaving the olde country, crossing seas and continents--remain conjecture, often colored by our own lives (what would I have done in that situation?).

In my case, my Irish relatives came to the US in the 1830s--long before the famine, and while there were some English and Scottish colonial period arrivals in the new world, some of my English relatives took a circuitous route to California, via Tasmania. (That they departed Tasmania for California in 1849 tells me that there was at least some economic motivation.). Some of hub's Prussian families were clearly fleeing the tough economics and threat of war in the run-up to 1848.

And so I go off with my own projections, and say I think it's usually a combination of seeking economic security, political or religious freedom, and love in a different place--moving to a place where we can be true to ourselves. In our own case, the decision to leave West Germany and come to the US was based on two things: there were no open positions for the career that my new husband had spent nine years preparing for, and being married to me meant that taking the risk of going to my home country was mitigated. For money and love.

|

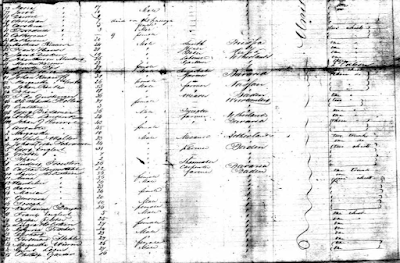

| 1850 ship's manifest: can you find the Hellsterns? |

No comments:

Post a Comment