In the 1920's, my Great Aunt Ruth Richardson came to Sutherlin, Oregon as a bride. One of her letters written back home to family in Northfield, Minnesota talks about when she went out to the springhouse to get some butter for her mother-in-law:

"And this is what I saw - shelves all the way around filled with jars and jars of canned fruit! I am going to offer to get the butter and cream every meal and count them.

"...Tonight I went after butter again, and I asked Mother Morgan if she would think me dreadfully snoopy if I counted the fruit jars. Now, darling, you simply have to believe me - there were six hundred quarts, and jars and jars of jam, preserves and chow chows, and a big immense jar of wonderful pickles. There were the most wonderful assortments of fruit, meat, fish and vegetables, and she had done it all herself. She is just so nice and modest about it; I'd think anyone who had done that ought to broadcast over the radio. And then she said in that nice quiet voice of hers that I am learning to love and respect, "But I canned a few more this year than usual." And what do you think she said? That two hundred of them were for us. Jim had bought the jars and sugar and she canned them."

The first time I met my husband’s aunt, she was in the kitchen of her farm in Southern Germany, cutting brown bits off a head of cauliflower, her fingernails blackened by soil and paring. My father-in-law did much the same with shriveled apples, taking them one by one from a cardboard box next to his chair. I recall being repulsed by the condition of the produce; indeed, it was the kind of stuff you would see in dumpsters in this country, never in the stores. But these people had been through a war on their own soil, and knew what being hungry was like. For my generation, who has lived in a world at war for nearly their entire life, there is no shortage, no hardship.

As I child I remember my mother parking close to the fence at the bank so my brother and I could stand on the hood of the car and pick blackberries while she did her banking. We had purple tongues when she returned, but there were enough for some on ice cream later, and even more that she turned into jam. She enlisted our help in stirring jam and canning peaches. In fact, on the day Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, we put up peaches: as the person with the smallest hands, my job was to neatly layer the cut and peeled peach halves in the mason jar so my mother could pour the hot syrup over them. When we cleaned out my parent's home, there was still one lone jar of "Moon Peaches" on a shelf in the pantry. They're past their prime, discolored with time, but I still packed them up (along with boxes of jars), and they sit on my pantry shelf with the other canned goods.

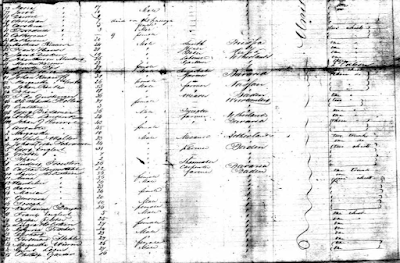

And there are more than a few, as my family and friends have learned that if they bring home fruit (or pick it from the trees on our suburban lot), jam will be made. As I take my first jam of the season down to the shelves in the garage where they reside, I check seals and rotate the jars (older jam near the door, newer jars on the left). I also took the opportunity to channel my ancestor and count the jars, and did you know, there were 126 jars of jam, and 36 of applesauce! I will share some with friends who have been trained to return jars, but my family will enjoy the lion's share of the bounty and I admit to a great deal of satisfaction from seeing them, rows of soldiers ready for toast.

Yes, there is jam available to us on the supermarket shelves and farmer's market, but we all prefer following in the footsteps of our predecessors and sweating through the hot days of summer so we can spread a little sunshine on our toast on a wintry morning.

.JPG) |

| Summer in a jar |